Content provided by Supporting Club member TypeTogether.

Understanding Devanagari Type Anatomy and the Broader Search for Typographic Vocabulary

Typography is not only about designing letters, it’s about understanding how cultures think, write, and give shape to meaning. Every script, from Latin to Devanagari to Arabic, carries centuries of visual evolution. Yet while Latin type design has long benefited from a shared vocabulary of form stem, shoulder, counter, serif, many scripts beyond Latin are still defining a common typographic terminology for the anatomy of its letters and their metrics.

Devanagari: The Architecture of Balance

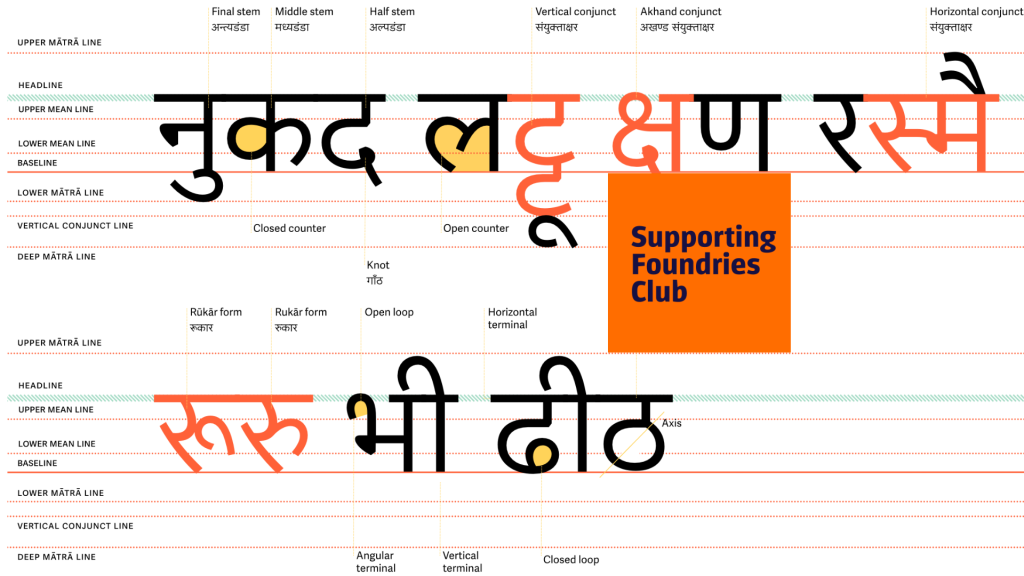

Devanagari the script of Hindi, Marathi, Nepali, Sanskrit, and several other languages is both structured, fluid, and human. For those new to it, the script can feel overwhelming: hundreds of glyphs, intricate conjuncts, vowel signs (matras), and marks that sit above and below a horizontal line. But, as Saxena writes in her article, what makes Devanagari seem complex is not its construction, it’s the absence of a common vocabulary for describing its anatomy.

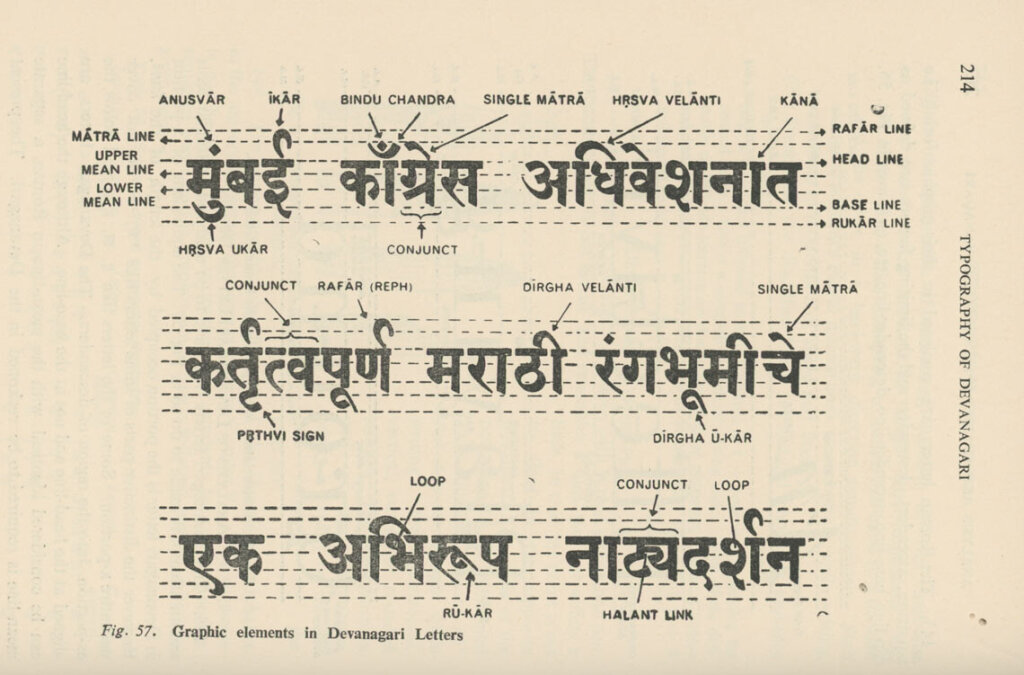

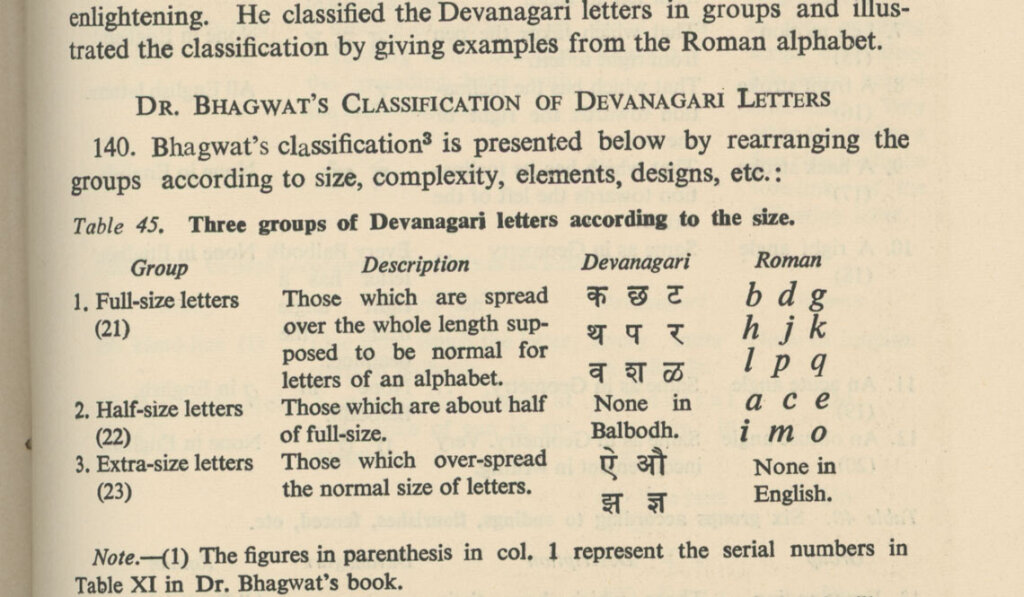

The foundation for such vocabulary was first laid by S.N. Bhagwat (1961) and Bapurao S. Naik (1971), whose Typography of Devanagari remains a cornerstone text. Naik divided letterforms into five categories based on their vertical stem and their relationship to the shirorekha, the horizontal headline that defines the script’s distinctive rhythm.

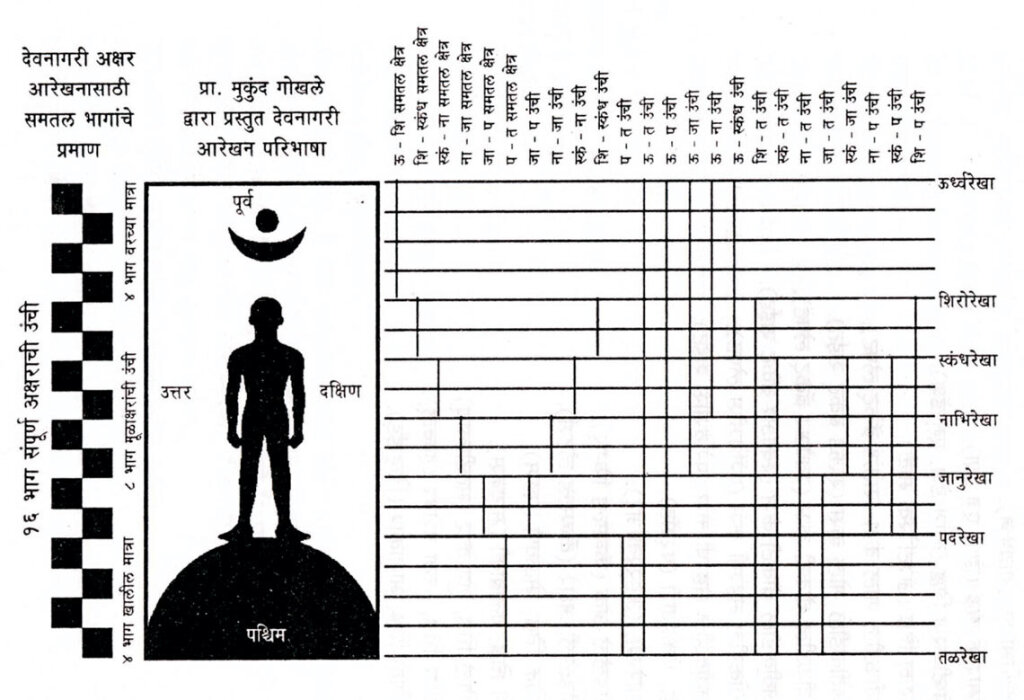

Later, Mukund V. Gokhale (1983) expanded on this, introducing a set of vertical metrics mapped to the human body:

Urdhvarekha - the uppermost limit, or “top line”

Shirorekha - the “headline” from which letters hang

Skandharekha - the “shoulder line”

Nabhirekha - the “navel line”

Padrekha - the “foot line”

Talrekha - the “bottom line”

This structure doesn’t prescribe rigid proportions as Latin’s x-height or cap height do. Instead, it forms a living framework, a set of spatial relationships that can flex with the script’s rhythm and tone. Devanagari breathes between its lines, not within them.

As Saxena notes, modern designers like Girish Dalvi have expanded this system, blending indigenous and borrowed typographic terms to create a multiscript vocabulary, one where loop, knot, counter, and axis coexist naturally with shirorekha and matra. This blending mirrors the global design environment itself: collaborative, translational, and open-ended.

A Shared Search: Arabic and Devanagari in Dialogue

In Azza Alameddine’s exploration of Arabic type anatomy, we find a parallel journey. Arabic, like Devanagari, was taught and transmitted through visual imitation rather than verbal instruction. For centuries, calligraphers relied on proportion, the rhombic dot rather than descriptive language.

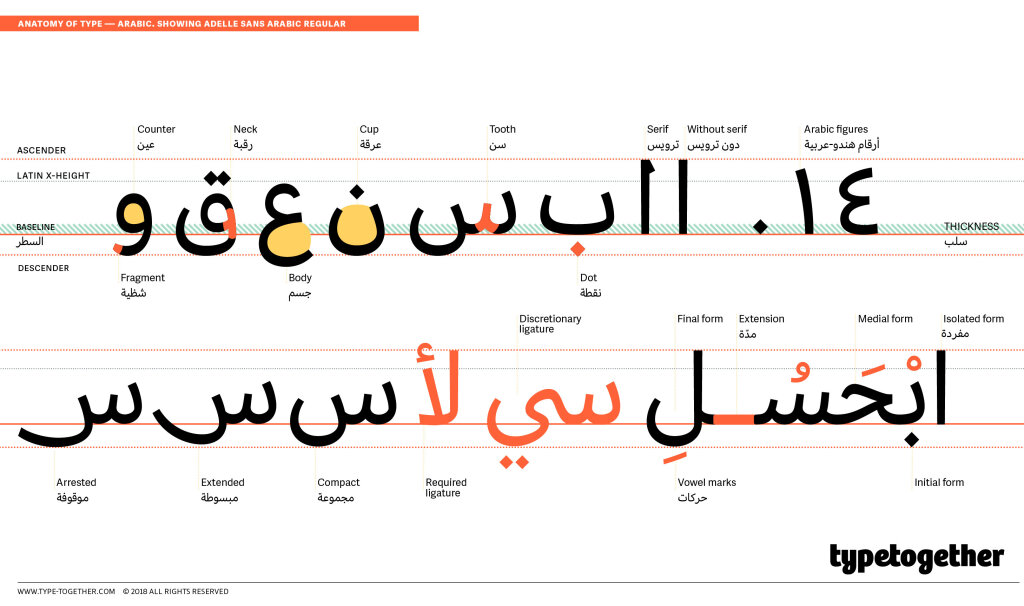

As digital typography emerged, Arabic too faced the need for a shared typographic vocabulary. Alameddine notes how designers began adopting intuitive, body-based terms: head, eye, tooth, neck, cup, giving shape to what was once unspoken.

Both Alameddine and Saxena, in different cultural contexts, explore the same question: How do we name the shapes of our languages?

Their search transforms anatomy into a kind of diplomacy, bridging oral traditions, historical scripts, and the technical needs of a global type industry. The effort to name a stem, a counter, or a knot is not merely academic. It’s a way of preserving how language moves, feels, and looks.

Through Saxena’s Devanagari and Alameddine’s Arabic studies, we notice a larger narrative that typography is both linguistic and cultural archaeology. It’s about unearthing patterns of visual thinking embedded in each script, and building a common ground where multiple systems can coexist without hierarchy.

Standardising terminology doesn’t flatten diversity, it enriches it. It gives designers, regardless of their linguistic background, the ability to collaborate, critique, and innovate. In doing so, it reaffirms that typography is a global conversation, one that must include all voices, all scripts, and all forms of writing.

Further Reading & References:

Devanagari Type Anatomy by Pooja Saxena

Arabic Type Anatomy by Azza Alameddine

The content of this article is provided by the Supporting Foundry Club member TypeTogether. GRANSHAN is not responsible for its accuracy or for any opinions expressed.