As part of GRANSHAN’s mission to celebrate global typographic diversity, we are launching a new interview series talking with GRANSHAN script experts.

Each conversation brings you closer to the creative minds shaping the future of the world’s writing systems - their stories, challenges, and visions for type design across cultures.

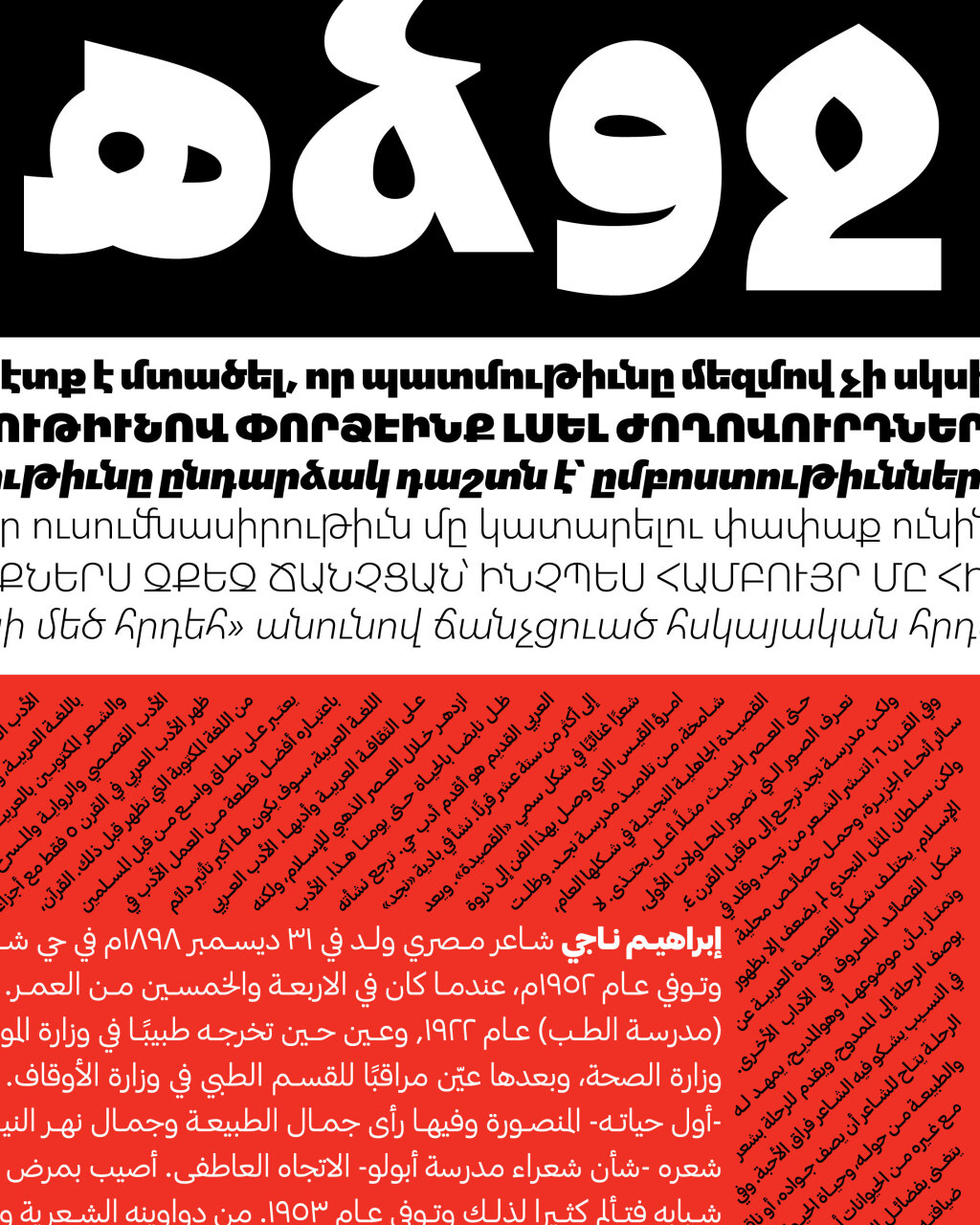

We are continuing with Khajag Apelian - a lettering artist as well as a graphic and type designer who works with Armenian and Arabic scripts. He moves between type design, research, and education and is interested in how design can keep cultural practices alive and relevant.

You are familiar with the Armenian and the Arabic type system. Do you prefer one of the two scripts?

Not at all. It’s not something I think about, to be honest. They’re completely different systems, and I like moving between them.

Arabic is one of the most widely used scripts in the world which cannot be said of Armenian. How many people use the Armenian writing system?

I would say that around 10 million Armenians exist worldwide, with three million in Armenia and the rest in the diaspora. However, this is an estimate, and there is no accepted consensus. You could assume that most of them use the script, but that’s also not accurate. Many Armenians from the diaspora don’t know how to read or write in Armenian; they barely speak it.

What is characteristic of the Armenian writing system?

The Armenian script has been used since the fifth century and carries a deep cultural and emotional significance. Its visual evolution reflects the many historical layers Armenia has gone through, including different rulers, shifting politics, and the split between Eastern and Western Armenia. Each developed under different influences. The Soviet period of the 20th century left a clear mark on how type was designed and taught, and today many younger designers are reacting to that history in their own ways.

The Armenian letters come from a long tradition of manuscripts and written forms. Later, the introduction of metal type brought its own logic and limitations. The digital era began in a rough way but has improved significantly since then. Over time, different stylistic tendencies have emerged, shaped by the tools and contexts in which people worked. Even today, you can sense the difference in how designers from Armenia and those from the diaspora approach certain forms. I find that variety interesting rather than conflicting. It shows how the script has remained adaptable while maintaining its Armenian identity.

»Armenian isn’t an isolated or niche script. It has a huge historical and geographical reach, and it continues to evolve.«

What are some unique or distinctive features of this script compared to others?

Armenian has a strong rhythm and a sense of modularity in how letters relate to one another. At the same time, it allows a lot of freedom. Many letters have multiple valid interpretations, and I like that there’s no fixed agreement on which is the »right« one. It depends on context and design intention. I also find it fascinating how printed and handwritten styles can seem far apart but still reveal a connection when you trace their development closely.

Armenian has 38 letters. Do the order and shape of the letters related to those of other scripts?

The Armenian alphabet was invented by Mesrop Mashtots. It’s said that he was conceptually inspired by the Greek and Syriac systems for connecting sound and symbol. Its letters and order are unique, making it one of the few alphabets created in a single period that has been preserved almost unchanged for 1,600 years. The main source of information about the script is the documentation of Mesrop’s pupil, Koryun. His writings suggest that Mashtots may have refined earlier local attempts, a mix of inventing and adaptating. There’s always been tension between the mythical story of the invention and the historical evolution. The general story that every Armenian knows is that the alphabet was divinely inspired, but it may actually be a synthesis of earlier written traditions.

You represent the Armenian script group at Granshan. How did you first become involved with Granshan and this script community?

I had just finished my graduation project at Type & Media in The Hague when someone encouraged me to apply to the Granshan 2010 competition. I didn’t know much about it at the time, but I found out on the last day of submissions, so I just sent my work. I was happy, Arek won Best Armenian Text Typeface and the Grand Prize across all categories. I was 24, fresh out of school, and Arek was my first typeface. The prize, the recognition, all of it meant a lot, especially looking back now.

I became more involved in 2016 when I attended the conference in Cairo. That’s when I started to feel like I was part of the Arabic script community. A year later, at Granshan’s 10th anniversary in Yerevan, I felt the same connection with the Armenian script community.

What is the current focus or priority of your script group?

Right now, it’s about visibility and continuity. We want to connect people working with Armenian type today, both in Armenia and the diaspora. There’s also a focus on education and creating platforms where designers and researchers can exchange knowledge and resources.

How does your script group support designers, linguists, and users of the script?

We try to connect people, share knowledge, and keep the conversation active between generations. A lot happens informally through workshops, talks, and mutual support. Granshan helps make that visible and brings together people who otherwise might not meet.

How can Granshan and the wider design community best support your work?

By focusing on sustained support rather than short visibility. Things like access to archives, mentorship, and long-term collaboration between designers can make a real impact. What also helps is maintaining spaces where people working with different scripts can share how they solve similar problems and learn from one another. That exchange keeps the field alive and evolving.

What are the major technical challenges in working with this script?

The main challenge is the lack of support from major global players. Arabic was in a similar position before, but things have improved significantly. I am often invited to work on Arabic type design adaptations of Latin fonts, but rarely for Armenian. When big brands or agencies commission custom fonts, Armenian isn’t even part of the conversation. On two occasions, I asked, and they answered that it’s a conscious financial decision because Armenian has fewer users. Still, it would be nice to feel that we exist in those global design systems.

Even something as simple as adding a dictionary would make a difference. I still can’t believe InDesign hasn’t added Armenian as a language for proper hyphenation. We often have to create our own tools to work around these limitations. In type design we work with Glyphs and the software handles most world scripts well. However, more resources and research would help. I’d also like to see more thinking around Armenian-specific technology. For example, vowel marks always sit above the letters, and the way they’re handled digitally could be improved.

So the script needs more public relations to become better known among companies and brands?

I think the biggest needs are education and infrastructure. We need more people designing, teaching, and writing about Armenian type. We also need better digital tools and resources to support that growth. But of course more public relations would help a lot. Sometimes I feel like Armenians have so many other issues, and making big brands aware of the script is the least of their worries. Some Armenians, if not most, might not even know it’s possible. Apple actually did it. They updated their system font SF Pro a few years back and we noticed the Armenian is no longer Noto. Ah that’s true, there’s also Noto Armenian, so Google was also kind to us once : ) And a lot of boutique foundries like Commercial Type, Dinamo, Type Together, Typotheque, etc. take always care of world scripts.

»We need more people designing, teaching, and writing about Armenian type — more education and better infrastructure.«

Perhaps we should start our public relations work by addressing any misconceptions about the Armenian writing system. Are there any?

Maybe that Armenian is considered an isolated or niche script. It’s not. It has a huge historical and geographical reach, and it continues to evolve. It has a lot of potential when seen as part of a larger conversation rather than a closed system.

What current or upcoming projects are you excited about?

I’m most excited to finish the Arabic type design workbook »Alternative pedagogy for Arabic type design« I started with Naima ben Ayed a few years back. We picked it up again recently and are hoping to finish it soon. There are also a few things cooking with the graphic and typedesigner Garine Gokceyan related to Armenian type and writing traditions.

You grew up in Dubai and Beirut, and did your master’s degree in The Hague. You currently live in Beirut, where you teach design courses in different institutions. However, the name of your company, Debakir (www.debakir.com), is Armenian for »printed type«. Where does your heart feel most at home?

I was born in Dubai. Then, when I was nine, we moved to Beirut, where I stayed until I was twenty-one. I completed my bachelor’s degree in Lebanon, after which I moved to the Netherlands to pursue a master’s degree in type design. I lived there for three years. Now, I live in Beirut. Why? Hmm... My whole life, I’ve wanted to leave Lebanon and never look back. I was about to immigrate to Canada in 2018, but I couldn’t because I realized that I belong in Lebanon the most. Then came the roller coaster ride through the economic crisis, the pandemic, and the explosion. I had to leave. I left for Yerevan thinking I would move there, but then the war between Azerbaijan and Armenia started. I was about to be drafted, but luckily, I escaped to Dubai. I stayed there for six months. Then I went to Mexico City to find a new home, and I stayed there for another six months. I went back to Armenia. I opened a business there and lived there for a year and a half. It didn’t work out. I realized that I do not belong in Armenia. As a Western Armenian, I found that there was quite a difference between me and the Eastern Armenians. Finally it’s been a year since I have been back and staying here in Beirut, despite it all, happily.

Interview by Antje Dohmann